Is tattooing an art form or a craft?

In the ever-evolving landscape of contemporary art, few mediums provoke as much debate as tattooing. Is it an art form, a craft, or something entirely new? The answer, as with all things that straddle the line between tradition and innovation, is far from simple.

Tattooing undeniably carries the hallmarks of craft. For centuries, it was a trade passed down from master to apprentice, steeped in ritual and technical precision. The skin, unlike canvas or clay, imposes strict limitations: it ages, stretches, scars, and fades. The tattoo artist must possess deep anatomical knowledge, technical skill, and an understanding of how pigment will settle and change over decades. Just as a master carpenter learns the grain of wood, the tattooer learns the grain of skin—its quirks, its vulnerabilities, its capacity for holding a line or blurring into abstraction over time.

This respect for boundaries has, for generations, defined tattooing as a craft. The unwritten rules—never overwork the skin, avoid excessive detail that will blur, maintain strong contrast—are not mere conventions but survival strategies for the longevity of the work. The best tattooers have always been those who understood the value of restraint.

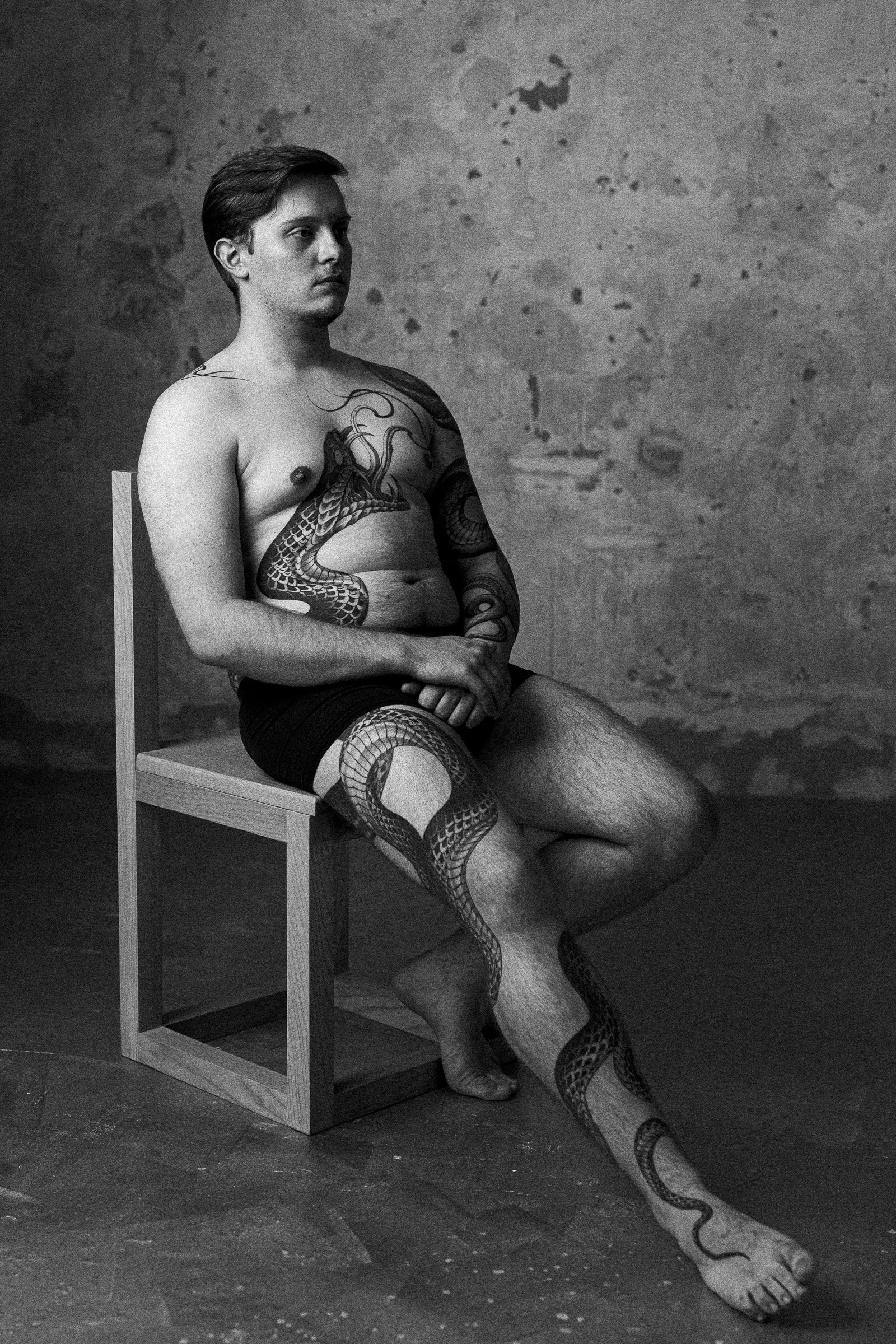

And yet, as with all living arts, boundaries are made to be tested. Every major movement in art history—from Impressionism to Abstract Expressionism—arose when artists dared to break the rules. Tattooing is no exception. The last few decades have seen the emergence of new styles, techniques, and conceptual approaches that challenge the very notion of what a tattoo can be. Artists are blending genres, experimenting with negative space, pushing color theory, and, most importantly, approaching the body not just as a surface, but as a living, breathing, moving sculpture.

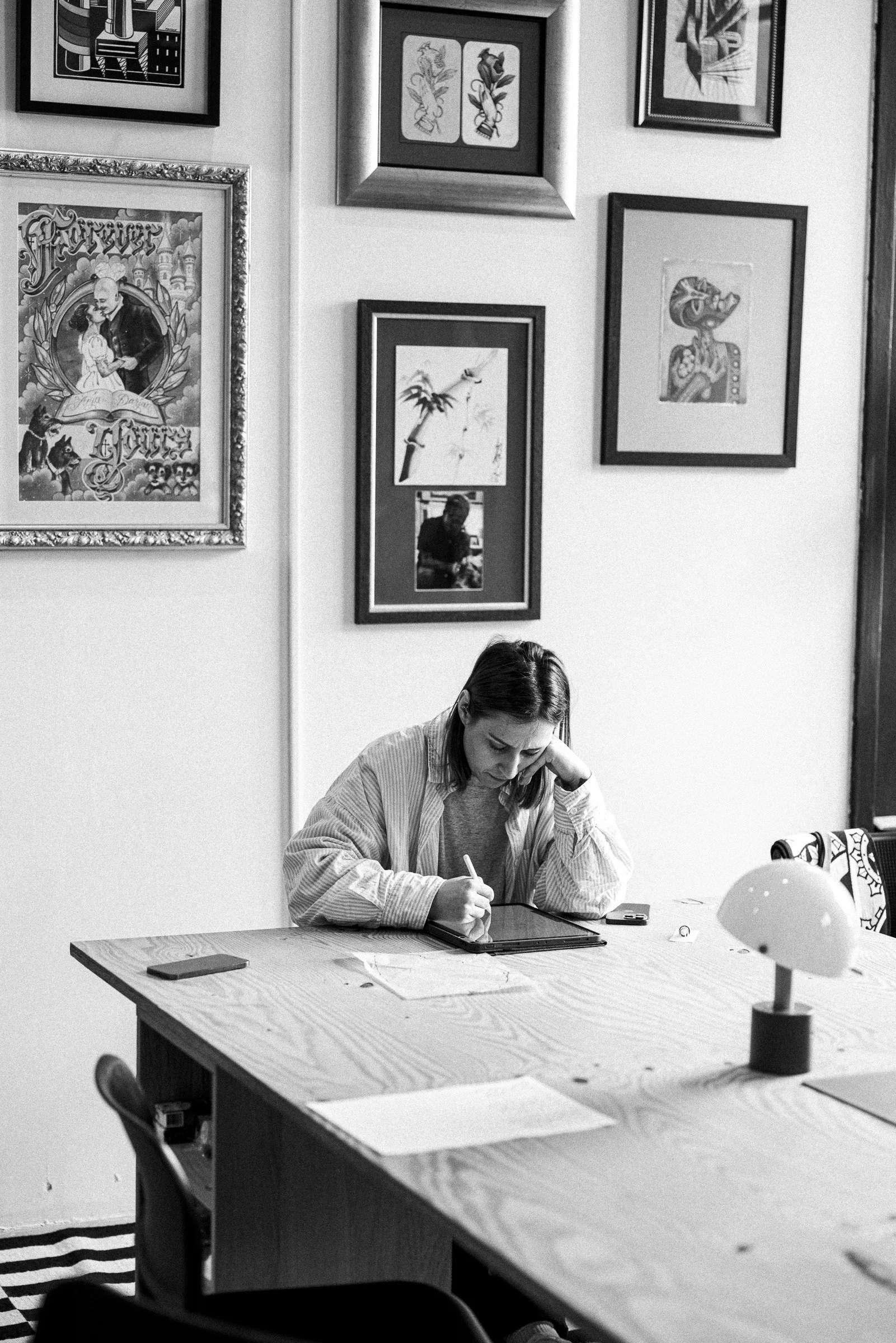

Herein lies tattooing’s unique paradox: it is both deeply personal and inherently collaborative. Unlike the solitary painter in their studio, a tattoo artist works with a living canvas—one that talks back, sets boundaries, and brings their own vision and vulnerability into the process. This negotiation between artist and client is not a limitation but a defining feature. The tattooist’s freedom is, by necessity, circumscribed; yet within those boundaries, genuine artistic expression flourishes.

Some critics argue that true art demands absolute freedom of expression, unbound by client wishes or practical limitations. But perhaps this view is outdated. Art, after all, has always been shaped by its context—by patrons, by politics, by physical constraints. What makes tattooing so fascinating is precisely this tension: the interplay between discipline and creativity, permanence and impermanence, tradition and innovation.

So, is tattooing art or craft? Perhaps it is time to recognize it as both—and as something more. It is a field in flux, a hybrid discipline that resists easy classification. As tattooing continues to evolve, it challenges us to rethink our definitions of art itself. The future will tell whether these boundary-pushing experiments will endure, but history suggests that every time artists have dared to step outside the lines, the world of art has grown richer for it.

What is certain is this: when approached with intention, skill, and vision, tattooing deserves to be taken seriously—not just as a craft, but as a vital, living art form in its own right.